The cover proclaims Phantom magazine to feature “true ghost stories” but does it? The editorial inside suggests that some of the stories claim to be true and some are fiction, but the editor decided not to clarify which was which, leaving that up to the reader to decide. This debut edition features no date, but inside an advert stating that the next issue would be out next month. That second issue sports a date of May 1957. That’s no guarantee that No. 1 appeared in April. It may have come out a month or two earlier. Undoubtedly UK fanzines discussed its appearance on the stands and I’d love to read their thoughts.

Phantom had a confusing publishing history. The first two issues state they were published by Vernon Publications and to send correspondence or manuscripts to Dalrow Publishing Company. By the third issue, both were dropped and Dalrow Publications was installed. The final four issues appeared via Pennine Publications.

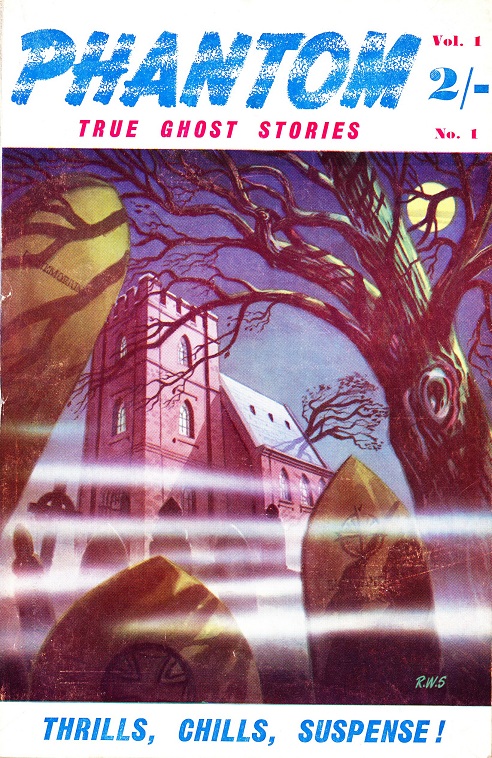

Phantom was priced at 2/- and was digest-sized, measuring 5.5 x 8.5 inches. The cover features a spooky building with wispy strands of fog across a cemetery and the cliche barren-of-leaves tree with a full moon in the distance. The artwork is signed R.W.S., short for Ronald W. Smethurst, and he was their only cover artist for the entire 16-issue run. No editor is listed, but we can probably assume it was Leslie Syddall, previously discussed while blogging Combat # 2 (December 1956).

Having read and indexed the other two Dalrow magazines (Combat and Creasey Mystery Magazine) I am fairly confident that the majority of the fiction in Phantom are reprints, the overwhelming majority of which have yet to be traced.

The Thing That Bites by Bernard L. Calmus introduces readers to Jerry Carder, a ghost investigator and paranormal specialist. Carder visits a remote haunted village with the intention of proving the paranormal events are fake but finds himself very much involved in a life-or-death struggle against a spiritual female vampire. Carder faces his fear of her and nails the lid shut on the case when he discovers the Countess and the vampire assaulting the young men in the village are the same. Our author’s full name is Bernard Leon Calmus. Following the second world war he edited Lifestream magazine and their series of “controversy” pamphlets. The British Library has some of his books, booklets, and plays. However, Bernard Leon Calmus was not his real name. In 1947 he renounced his birth name of Barnett Laab Kalmus. I found the above story to be a simple, easy read, and enjoyable, even if lacking in detective work. Did the story originate within issues of Lifestream, or some other unindexed publication?

In The Permanent Tenant, Primrose Townson presents readers with a “possession” or “soul transference” tale. Couple of guys room at a remote location in Yorkshire. They discover a recluse also rooming. They are given to understand he is a professor or some-such nonsense, but they are convinced he’s an escaped convict. Much time passes when one day they hear a person in pain. They discover the recluse on the ground, having likely slipped and bonked his noggin. One of the guys claims to have expertise in the occult and wishes to see if he can transfer his soul or essence into the unconscious man. Moments later, the recluse comes running into the room screaming for his friend’s help! It’s clear the man is speaking via his friend. He falls down and seems to die. Mortified, he runs into the room and finds his own friend dead. A verdict is returned of heart failure. And the “dead” recluse? Alive and doing well. A rather weak tale. No explanation is given as to how the man transfers his soul or mental being into the mind of the recluse. Primrose Townson was created by the editors of Phantom to hide the fact that they had actually nabbed six stories by one authoress: Mrs. J. O. Arnold. This tale, like all six of hers present in this magazine, come from the same source. The Permanent Tenant was published in the Derbyshire Advertiser and Journal (21 February 1930) as part of their Estrange Experiences series. I don’t know if this was a syndicated feature or if the Derbyshire Advertiser and Journal were the first to print the tales.

Mrs. J. O. Arnold was an author during the early 20th century, with novels such as Fire I’ the Flint (London: Alston Rivers, 1911) and Megan of the Dark Isle (London: Alston Rivers, 1914). Her real name is Adelaide Victoria Arnold (née England) and the alias stems from her husband’s name, John Oliver Arnold, whom she married in 1883. Adelaide was born in the 3rd Quarter of 1860 and died during the 2nd Quarter of 1933. She wrote about a dozen novels spanning the 1910s-1920s. Online source state that many of her later works had a supernatural slant to them. This excites me as some of her short stories have been traced to pulps and other popular publications.

George Burnside’s The Ginger Kitten is a bit more difficult for me to explain. Horror aficionados will have to correct me here, but the tale involves an older wealthy woman and maid/servant. The woman hates cats, among other things. A ginger kitten with green eyes shows up one day, uninvited. Much as they try, the kitten keeps coming back. The maid apparently likes the cat and suggests they keep it to kill the mice. The woman relents, but soon, strange happenings occur. Worse, the maid eventually states that there is too much to do and must leave unless they obtain additional help. Soon a ginger-haired woman with green eyes answers the call and performs her duties. But, she seems contrary to the woman at times. Not directly, at first. Then the cats begin to appear. A steady stream then a torrent overtake the home. Plus, milk and food disappear. The woman stays up one night and listens for noises. She eventually hears noises and goes down to investigate. She hears snarling / growling noises and stumbles across the second maid. She runs for her life and later confronts her concerning the stolen food. She denies the charges yet there is milk smeared on her, etc. She is fired and the cats all vanish from the premises. Was the ginger kitten her familiar? She clearly became cat-like at night and hostile. George Burnside is yet another posthumous alias for Mrs. J. O. Arnold. The Ginger Kitten was published in the Derbyshire Advertiser and Journal (7 March 1930) as part of their Estrange Experiences series.

Another Man’s Fear by Gavin Williams had me at first thinking I was about to read an Edgar Allan Poe pastiche to The Tell-Tale Heart, but I was wrong. A very old lady in an apartment nightly plays loud music on her record player, ancient music. She continually has health issues, and her younger neighbor takes it upon himself to assist in scheduling her doctor appointments. Then one day, she is gone, and a new tenant has moved in. The fellow is trying to move the massive wood-framed bed across the room because he hears an obnoxious noise, a dripping sound. Our fellow doesn’t hear a thing. Every Thursday the new fellow hears the dripping, and it slowly drives him insane. Even moving out and with a friend, he is powerless to resist the call and returns to the bedroom, the drip. He eventually rams a pair of steel scissors into his breast and kills himself. To his horror, the neighbor now hears the drip, but claims it is only the dead man’s blood dripping through the mattress to the floorboards. And suddenly, he realizes the room indeed has some form of evil residing. An unusual horror story with no real ending. Was the man “mad”? Or could he really hear the dripping? Did the old lady, the prior occupant, also hear the drip, and is that why she played her ancient records loudly? This sort of horror story makes for good night-time reading or a camp-fire tale. I’ve no clue who Gavin Williams was; he is not the very same named person that contributed horror fiction and articles during the 1990s and to the film industry. But could they be related? FictionMags shows that our Gavin Williams had one further story in the 12th issue of Phantom. I’ll look forward to reading it.

The Best Bedroom opens with the narrator (or author) stating: “this is not a ghost story, rather a strange psychic experience.” Thank you for the clarification, Mrs. Arnold. And she didn’t lie. A wealthy woman and her chauffeur stop at a countryside inn after her car suffers mechanical problems. Refusing a room with a leaky roof, she’s given the family’s ancient “best bedroom.” Unfortunately, it has a history of scaring all residents. She immediately feels a psychic energy present but is confident that she can conquer it. Falling asleep in the massive bed, she awakens to the horror of being in suspended animation, reliving the horrors of a woman who died after being removed from the room and entombed alive in a coffin. She finally breaks free and faints. Ordering the matron to relay to her the females who died in the room, she finally lands upon the one who’s terror she suffered through. A pleasingly gothic / psychic horror story. The Best Bedroom appears in the Derbyshire Advertiser and Journal (31 January 1930) as part of their Estrange Experiences series.

In Terence Kitchen’s The Tenth Notch, a young man is invited to stay with Major Randall and his Afridis servant. Moving into a newly acquired Hawthorn Cottage in Sussex Downs, the major has his servant unpacking weapons from his war campaigns when a kukri slips free of its sheath. The major relates that it belonged his faithful Gurkha soldier who died in combat, while discussing the Tirah campaign of 1897. Sadly, the man never had the opportunity to slip his kukri free before dying. The visitor notes it has nine notches. Later that night, while the major is asleep, he walks into the leisure room to find the servant still unpacking and polishing the weapons. In the mirror over the fireplace, our young man is mortified to see a dark-skinned man reaching across the servant. Spinning about, he sees nothing. His imagination? Going to sleep, he rises the next day, walks in the room, and finds the man cleanly decapitated, the kukri bathed in blood, and sporting a tenth notch. The entire story is related to the reader from the man’s own notes of the case, which he did not related to the police for fear they would lock him away. He realizes the ghost of the Gurkha had returned to slay his enemy, for as the major had related, once their kukri was unsheathed, they must kill their opponent. Terence Kitchen is yet another alias for Mrs. J. O. Arnold. The Tenth Notch was published in the Derbyshire Advertiser and Journal (7 February 1930) as part of their Estrange Experiences series.

Perhaps one of the better constructed tales yet, Barney Gunn’s The Hungarian Wine Bottle takes place in 1930s Hungary, after Hitler has come to power. A newshound decides not to return without a different sort of story for his paper. After the author relates to us a lot of ancient war history, including a new explanation for why the cross on the crown is crooked, the newshound decides to investigate a tunnel that leads from a castle and under the river that saved the locals from the Turk invasion. The locals refuse to discuss the tunnel, fear etched on their faces. Sneaking in and down the steps to the cellar floor 30 feet below, he comes to an old wood door with rusty hinges and an ancient, oxidized padlock. He can’t break through the door nor break the lock after repeated attempts. Giving up, he’s greeted with an unusual sound. The door falls off the hinges towards him as he backs to the stairs. His candle is blown out. Striking a match, he enters the damp tunnel and discovers an old wood wine bottle, corked. Popping the cork free, for their is liquid inside, he goes to sniff it when a hand falls upon his shoulder. Turning, he beholds a young lovely lady in old clothes. She doesn’t speak a lick of English, but follows when she leads on with her lamp, which he thinks unusual that only his own tiny candle gives off any light. They come upon a wounded soldier. Taking the wine bottle from him, she pours liquid into the man, but he does not revive. Distraught, she hands the bottle back to the newshound and he realizes the candlelight is pouring right through her body! She blows out the candle and he feels as though someone has bonked him on the head. Awaking, he finds himself outside the tunnel, the door still perfectly sealed, himself at the foot of the steps. Did he imagine all of it, accidentally slip on the steps, and concuss himself? Escaping the castle, he retreats into town and runs into the other news sharks, who want to know where he’s been and who was the girl. Say what? He discerns he’s actually been missing for a whole day, and a small replica of the wine bottle is in his possession! Ever since that moment, he is with the replica and no harm befalls him. Entering WW2, he is gravely wounded and slated to die. His wife brings him the trinket and he has a full recovery! Re-entering the war, with the trinket undoubtedly bestowed upon him by the ghostly girl as a good luck charm, he finds that bullets and bombs do him no harm but everyone to the left and right of him are slain. So, what precisely is protecting him? The trinket? The soul of the girl?

I have to confess, when our narrator pulls the cork, I was expecting a djinn, not a ghost. What precisely the wine bottle has to do with the entire episode is unclear, save as a prop for the rest of the story. Frustratingly, I could not locate anyone by the name of Barney Gunn alive in England.

The Cupboard is by Cecilia Bartram and there appears to have been two ladies by this name alive in England. The first was born in 1896 and died 1967 in Yorkshire. The second was born in 1921 in Yorkshire, married Frank Tingle in 1942, and death date is unknown. It is quite feasible that the second lady was the daughter of the first. The fact that they were both born in Yorkshire is important given the story takes place in Yorkshire! All for naught, our author is neither lass. It’s once more Mrs. J. O. Arnold! The Cupboard was published in the Derbyshire Advertiser and Journal (28 February 1930) as part of their Estrange Experiences series.

The story opens with the authoress as “Mrs. Bartram” meeting with fellow wealthy elitists. She has a habit of entering all manner of contests and notes that the current entry is for an “unusual experience.” None of those present offer a genuine bit save for one chap who claims to have psychic abilities but avoids the occult. He relates an old incident in which he was bicycling in the Yorkshire moors when a nasty winter storm descends and the snow and chill is too much. He seeks shelter at a cottage, knocking repeatedly. A potato farmer lets him in. Coming to terms over bread, cheese, and an old bed in the attic for the night, our psychic turns in for bed but spots a tall, padlocked cupboard in the room. Later, he discovers a key, and an irresistible “pull” to open the cupboard. He does and finds himself beholding a redhaired man hanging inside suspended from a hook. Mortified, he locks the cupboard, runs downstairs that next morning, jumps on his cycle and pedals on his way. On the way into town, he runs into the potato farmer and another man returning at a fast pace. Inquiring if he found a lost key in the attic, he acknowledges indeed he did. The farmer then accuses him of stealing his cash in the cupboard, but the psychic remarks upon the dead man instead. Both farmers are surprised, and the pair return to the cottage, open the cupboard, and…no dead body. The hook is present. And so is a small box with the farmer’s cash all inside. The pair inform the psychic that where he stayed is known as Hanged Man’s Cot, as a man did just that 50 years earlier and the psychic isn’t the first to have seen him!

Next up is a second story by Bernard L. Calmus, being The Howl of the Werewolf. The setting is the tiny village of Tille, France. A terrified young lady is running for her life and Inspector Lineau spots her in the woods. Grabbing her arm, he secures her and forces an explanation. She relates that while walking in the woods she saw a shadowy figure that appeared to be in pain. She then witnessed it turn from a man to a wolf. Lineau spots the sinister form but can hardly credit his eyes. A wolf, here? Certain they’d all been eradicated hundreds of years ago, he’s nonplussed. But when they hear screams, the pair find another person ripped to shreds, the local “poacher”, and his stolen rabbit on the ground untouched by the wolf. Escorting the Ms. Grande to her father, an occultist, they find another person already at the doorstep, knocking. Her father opens the door to admit Gerard Kerch (whose name reminds me of author Gerald Kersh; coincidence?) and then in walks Inspector Lineau with the girl. They relate the facts as they know them and her father suggests it was a werewolf. More deaths occur in typical sensational style. The story concludes with Kerch shaken when his betrothed is brought in on a stretcher, bloodied and very dead. He’s certain the girl’s father is the werewolf, after all, he is always pale and weak and then seems alive and vibrant after each death. Calling to the townspeople and conveying his feelings, they grab weapons and storm Grande’s cottage, dragging the man out to be hung. Grande claims to know some secret incantation to reveal the werewolf’s true identity, forcing it to transform. Kerch remarks this is idiotic and yet, Grande utters the words (whatever they are, the author doesn’t reveal) and suddenly, to no reader’s surprise, it is Kerch who transforms. The village people, already incensed, go insane and batter the werewolf. The girl begs Lineau to use his service revolver to put Kerch out of his misery just as a fireplace poker bangs down upon Kerch’s skull. Lineau inserts himself and kills Kerch.

Thomas Narsen is our final guise for Mrs. J. O. Arnold. The Tank was published in the Derbyshire Advertiser and Journal (14 February 1930) as part of their Estrange Experiences series. I’m beginning to think I ought to locate some cheap copies of her assorted supernatural novels. Has anyone ever read her books? I’d love to hear your thoughts about her stories. A ruined relic of the War (aka: The Great War, aka, WW1) is given to a seaport town but they don’t want it. “It” is a demolished wreck of an English tank. Relocated inland to an isolated town, the war survivors find it interesting. None of them served in the tank corps but have stories surrounding them. Then, one night, at the local pub, one tells tales of an eerie blue light emanating from the tank on the hill. Doubters call him drunk or fun him, but when a “tramp” steps forward and informs one and all dead-sober he’s not only seen the light but heard voices singing their old war hero tunes, the laughter dies away. The town distrusts tramps (foreigners) and the narrator interrogates the man. To him, he finds the man indeed did serve in the War. Time passes and the tales grow worse and more and more see the blue light and hear the singing. They are fearful of the tank. The narrator decides to investigate at night with his lantern when the “tramp” runs up to him, begging him not to go. He confesses that he created the light and singing. Why? Well, tramping along, penniless and homeless, he was surprised to see the tank. Recognizing the tank’s number as one intimately, he relates that everyone inside died during the War. Taking advantage of the opportunity, he set inside as his temporary home and haunted it to keep snoops away. Only one problem. The tank’s dead took on a life of their own. Terrified, he runs away in fear and the narrator continues up the hill. His lantern’s light goes out (claims it ran out of fuel) and the blue light flames up and the singing commences. Nothing inside this time is causing the occurrence.

Her Eye on the Shadows is a two-page tale by married couple Patricia (Pat) & Peter Craig-Raymond. The protagonist is Angela Laine, and the story takes place in 1956. For the past year she has painted and rapidly sold a dozen identical “dark” paintings. They aren’t her style. Something or someone else has been possessing her hand, paint, brush, canvas, but signing her name to the works. She knows she has just finished the last work and is forced to pick up a thin blade and thrust it deep into her breast. That the tale takes place in 1956 is important as it firmly dates when the story was likely originally published, but the source is currently unknown (by me). Peter Craig Raymond (no hyphen?) was born 12 December 1931 and married Patricia (Pat) Lutley-Sandy in 1952. Peter wrote articles, was a magazine editor, wrote books, was a television host, a land investor, involved in football, and was as of the early 2000s, still alive. After which, I lose his trail. He’s credited with editing Beautiful Britons, a gentleman’s magazine published by Town & Country during the 1950s with photos of girls. There are also four books to his credit: one on English dancer Roland Petit (Losely Hurst Publishing, 1953) and a book on an English dancer, Victor Silvester’s Album (Centaur Press, 1955), and two further concerning dancing, being Your Child in Ballet (Ballet Publications, 1954) and So You Want to Be a Ballerina (Colin Venton, 1956). All of which leaves me bewildered that I can’t solidly place my finger on the author’s identity. So, four books on dancing, and editor of a gentleman’s magazine of English lovelies? He also contributed articles to Ballet Today. 1960 he is listed as managing director of Triumph Foundations. A 1961 article notes he just returned from New York City with his “actress wife” Pat. Then in 1962 he seems to have formed the Sumnorth Property Company which suggests PCR was trying to sell land or investment opportunities in Brazil! Another article in conjunction with the Brazil land-offer suggests he is a wealthy football (soccer) fan and was a team manager. He turns up on the British Film Institute site as a presenter to the television series Stars in the West for 1961-1962. The married couple had 3 children: Lee Craig-Raymond (1952), Vaune Craig-Raymond (1956), and Tay Orr P. Craig-Raymond (13 May 1968, dead 1979). Vaune married Barry Hodgetts in 1981 and Lee married Alan Lewis in 1987.

Alan Crooper supplies I Wore a Black Ring! and the tale initially takes place during WWII. The unnamed narrator is a radar officer in the R.A.F. and stationed on Akyab island, which is near Burma. He’s assigned to maintain cleanliness and tries to assign the duties to various Indians with little luck. Nabbing a Mahratti, he orders him to clean the latrines. Days later, he learns the man hasn’t done the job at all. Days later, our narrator is posted to Ceylon and discovers the same Mahratti present, trailing him about. Eventually the pair come together, and the Mahratti presents him with a black elephant hair ring, stating it will give the wearer good luck once, and then it will be returned to the Mahratti. Say what? “It” will return to the original owner? The man doesn’t want it, but refusal would be an insult. He slips it on and discovers that he can’t take it off, no matter what lubricant he tries. Time passes, the war ends, and he hooks up with some old mates and they decide to go rock climbing. Obtaining their gear and wheels, they begin their adventure. Only, the car continuously finds all manner of ways to not cooperate. Tire problems, engine problems, steering column woes, etc. It’s an absurdity of calamities which begin to wear on the reader (myself) as the story progresses from the Weird to the Comedic. I don’t fancy the two together, unless it’s entirely clear the story is meant to be a comedy. They eventually come across a car looking for a tow; they tie their climbing rope to the car and tug it along. Only, the rope splits! They discover the rope was damaged and had they used the rope to climb, as intended, they’d either come to harm or likely death! Returning home, the narrator’s wife asks what became of his black ring. He’s stymied. When did he lose it on the journey? Matters come to a head when he receives a redirected letter, sent to him from the Mahratti explaining he’s happy to have his ring back and that he’s glad that it performed its function pleasantly for the narrator, who now realizes the black ring saved his life. Now, there does not appear to ever have been anyone by the name of Alan Crooper in existence. I suspect this story was originally published in Singapore, Burma, or somewhere else in that region of the world, but who knows?

F. J. Taylor’s The Empty Platform is a two-page vignette; the narrator discovers he likely was arguing with a ghost as to what time a train would arrive. He learns from the ticket collector the time in which the ghost requested hasn’t arrived in years since a train accident. He recalls the incident well for a man was waiting on the train platform for his love to arrive. When she died in the smash-up, he committed suicide. The story was reprinted in the 7 February 1959 edition of the South Yorkshire Times and Mexborough & Swinton Times.

River Mist by K. S. Choong debuted in the Sunday Standard (Singapore) 15 January 1956, originally as The Monster of the Highlands by Michael Choong. The tale opens with Abdul explaining events leading up to the deaths of three Europeans to police investigator Corporal Ramir. One female and two men are dead. Abdul relates that he overheard their entire conversation the prior day. The woman had claimed to have heard voices commanding her to leap through the mist into the river below. This would be certain death. Local lore suggests a serpent or prehistoric being lives in those waters. The one man believes her story and wishes to investigate. She begs he doesn’t. The doctor suggests she hears nothing but her own desires. Abdul suggests that no mysterious being actually slew the trio. He thinks the older man slipped, fell, and died. The Corporal indeed notes he has a broken leg and could have died as suggested. Abdul then suspects the woman lost her mind, picked up a large rock and clubbed the other over the head. Then she killed herself. Corporal Ramir suspects otherwise and states Abdul is a liar and a thief, that he snuck up and killed all of them for their money, as he has a history of being a noted liar. Abdul panics, steps back away from the Ramir, and falls through the mist to his death into the river. Mingled with his dwindling screams, Ramir is certain he hears another noise. His imagination, or, is there really a supernatural presence?

K. S. Choong and Michael Choong are both aliases for Choong Kok Swee and he was born 9 September 1920 in Penang, Malaysia and died in 1987. He was married to Barbara Joo Keong. He received his education at St. Xavier’s Institution. Monsoon Magazine editor and publisher in 1945. During the 1950s he was editor of the Pinang Gazette and the Pinang Sunday Gazette. His wife in 1955 won the $2,500 prize contest for solving a puzzle in The Straits Times. In 1971 he was the first editor-in-chief of Malaysia’s The Star newspaper which was modeled on UK’s tabloid The Sun. The oldest fiction story I’ve traced by Choong appears in Singapore’s Sunday Tribune (18 May 1941) titled The Dead Cert.

The rear cover features the poem “Witches Song” by Tiberius. Its earliest known publication was the British magazine Weird World No. 2, 1956. However, while both editions feature the same text, confusion arises when I discovered that a later edition surfaces with twice as much text! The later publication appears on Page 18 in Essayan (Summer 1962), a magazine for Eccles Grammar School. The poem is titled Witches’ Song but it is not credited to Tiberius; it credited to student “D. Brown”. I’d love to track down the student and ask them where precisely they located this longer version. Eccles Grammar School no longer exists; it was merged into another school. I wrote them but [sadly] never received a reply.

Now, a “Tiberius” did turn up in the American literary magazine called Driftwind, which is notable for having published poetry by H. P. Lovecraft. Most of those issues have never been indexed. Could our Tiberius be from this publication?